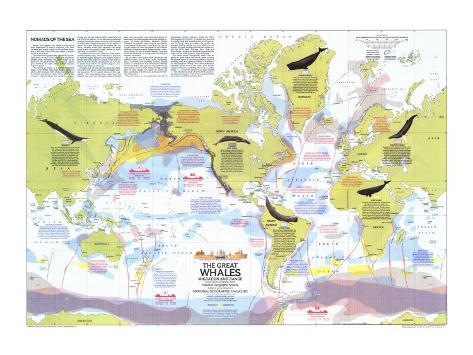

Nomads of the Sea

Despite their gigantic size, whales are among the least understood of earth's creatures. they exist untamed and usually unseen in the trakless ocean, only in the past century has man begun to fathom their lives and travels.

This National Geographic map represents an ambitious effort to chart their ranges and migrations. Shaded areas distinguish the home waters of six species of the great whales: fin, humpback, sperm, gray, bowhead, and right. ...

The hunting of whales as a commercial pursuit began in the Middle Ages when Basque seamen in small craft harpooned right whales migrating down the French and Spanish coasts. Shore whaling also existed in medieval Japan, and spread to northern Europe and the east coast of North America by the end of the 17th century. In the 19th century deep-sea whaling boomed as a major enterprise, with hundreds of sailing ships ranging the oceans. At the sight of a spout, oar-driven boats would be dropped into the water. Whalers armed with harpoons and lances would attack the powerful beast, whose oil would light their countrymen's lamps.

In modern times the scene shifts to a swift, diesel-powered catcher boat, from whose bow a man fires an explosive-tipped harpoon into a hapless whale. A factory ship then strips the carcass in less than an hour for its tons of meat earmarked for use as human or animal food, and its oil, used in margarine, cosmetics, and industrial lubricants.

Ironically, most of what we know about the whales' movement and habits comes from this deadly whaling experience. The six species already mentioned, together with the prodigious blue whale, have long stempted man with their abundant yields of oil and meat, and, as a result, have lured ships across the seven seas. From these voyages have come valuable accounts of whale distribution. Zoologist Charles Townsend, for example, made a singular contribution to the study of whales when, in the 1930s, he charted in great detail the times and places of kills made by hundreds of whaling vessels. Tagging studies, undertaken during the era of modern whaling, have also furnished information on the direction and timing of cetacean movements.

By the 1940s many great-whale populations had suffered serious, and in some cases, devastating losses. Confronted with dwindling numbers, whaling nations in 1946 formed the International Whaling Commission (IWC). This agency is responsible for the conservation of the world's whales through hunting bans for some species, kill quotas for others, size limits, monitoring catches, and exchange of scientific information.

The self-interest of its membership and lack of enforcement poswers, however, limited the IWC's effectivemess until recently. In the past five years the 16-member body has lowered quotas by 40 percent, and the Soviet Union and Japan, the world's two principal whaling nations, are now abiding by the ceilings. The major whaling countries that remain outside the IWC – Spain, Portugal, Peru, Chile, and South Korea – account for less than 10 percent of the catch, and are under pressure to join the league.

The latest quotas theoretically assure that all species of great whales will surivive. What probably will become extinct is the whaling industry, victim of the mounting costs and a growing number of substitutes for whale products. Perhaps then, Herman Melville's estimation of the whale as the earth's more durable creature will prove something more than a heady dream: “... if ever the world is to be again flooded ... then the eternal whale will still survive, and rearing upon the topmost crest of the equatorial flood, spout his frothed defiance to the skies.”

PROTECTION - Bowhead, right, and gray whales are designated as “protected” by international agreements in the 1930s. The humpback and the blue gained full protection in 1966. Most current information comes from sightings by whalers seeking fins, sperms, or smaller species. Since such sightings are incidentedent, not systematic, actual ranges and counts are no doubt larger.

EQUATORIAL BOUNDARY - Because great whales seldom cross the Equator, populations within a species are often identified as either Morthern Hemisphere or Southern Hemisphere. Most whales follow a season cycle of feeding in cold latitudes in summer and breeding and calving in warmer latitudes in winter. Seasons are reversed in the two hemispheres, so both populations move south at the same time; mixing of the two groups in thus unlikely.

ALASKA ESKIMO WHALING - Mixing traditional and modern whaling methods. Eskimos hunt bowheads during their spring and fall migations – a practice going back to 1800 B.C. the U.S. Marine Mammals Protection Act of 1972 exempts native subsistence hunters from the nation's ban on whale killing.

CANADIAN ARCTIC WHALING - Canada's Arctic peoples hunt the smaller toothed whales–narwhals and belugas–and kill an occasional bowhead.

GREENLAND WHALING - Small-boat fishermen, equipped wit hahrpoon guns, pursue small whales, maily nimkes,Nativer hunters killafew humbacksandanoccasionalfinor bowhead.

ICELAND WHALING- Iceland's industry operates under strict government controls. Eachyear it takes several hundredfinsandseisand fewer than 100 sperms.

AZORES AND MADEIRA WHALING - Whalers from these Portuguese island groups still hunt sperm whales with harpoons thrown from small boats. This outmoded method remains effective, as a yearly kill of about 300 attests.

CARIBBEAN WHALING - A small fishery at Bequia, in the Lesser Antilles, occasionally manges to kill a migrating humpback, whose meat and oil are consumed locally.

SPANISH WHALING - Coastal whalers take a toll of the local stock of fins. Spain, not a member of the International Whaling Commission, kills 150 to 200 sperms and fewer than 100 fins a year.

BRAZILIAN WHALING - Whalers harpoon some fifty sperms a year. The main quarry, however, is the much smaller minke whale – up to several hundred annually.

SOVIET QUEST FOR GRAYS - Ships of the Soviet fleet yearly take between 100 and 200 gray whales of Siberia. The International Whaling Commission allows governements to harvest protected species on behalf of aboriginal peoples. The Russians deliver the whales to coastal settlements, where the meat and oil augment native subsistence.

FIN WHALE - Huge,fast, and valuable, the fin wander through most oceans; only the known population centers have been charted. Because of their wide range and relative abundance, they best represent other members of the streamlined genus Balaenoptera: the great blue whale, the sei, the Bryde's, and the minke. Second only to the blue in size, the fin experienced grave losses in the 1950s. Down to about one-fifth of its original population, fins now number about 80,000 in the Southern Hemisphere, more than 15,000 in the North Pacific and fewer than 10,000 in the North Atlantic.

FACTORY SHIPS - The floating factory, attended by catcher boats and spotter aircraft, can pursue whales to almost any place in the oceans. The Soviet Union and Japan have adopted this method of hunting and take 85 percent of the world's whale catch.

SOUTH KOREAN WHALING - Ignoring international quotas, South Korea takes a few fins and hundreds of minkes each year.

JAPANESE WHALING - Whaling still playsan important role in Japan'scoastal fisheries,complementing the hunting waged on the high seas. Shore stations annually take some 2,000 sperms, together with Bryde's minkes, and other smaller whales.

AUSTRALIAN WHALING - Ashortage of whales and a ban on killing humpbacks combined to tclose all but one of Australi's whaling stations. The remaining station, equipped with three catcher boats and a spotter plane, lands about 1,000 sperm whales annually.

WHALE WATCHING - Both scientific and amateur curiosity about whales multiplies yearly. A small wintering herd of humpbacks in Hawaii now attracts dozens of scientists, photographers, and whale enthusiasts. The gray whalers that follow the west coast of North America to and from their breeding ground in Baja California are often “chaperoned” by well-meaning observers. Cetologists worry that this commotion may drive whales from their chosen migration routes and breeding grounds.

PERUVIAN WHALING - Each year the Peruvian whaling industy kills about a thousand sperms, a few fins, and hundreds of the smaller species.

CHILEAN WHALING - Chile's coastal fishery captures more than 100 sperm whales a year and a few fins and seis.

HUMPBACK MIGRATIONS - Tagging studies enable investigators to unerstand the movement of the southern humpback better than any other group of great whales, with the possible exception of the eastern Pacific grays. Traveling at a leisurely pace–about five knots–the humpback follows relatively narrow paths between its polar summer grounds and tropical winter home.

HUMPBACK WHALE - The tendency of the humpback of cluster around islands and hug shorelines has madeit one of the easiest whales to hun. contnt exploitation by coastal fisheries lef only small, apparently isolated stocks. this slow, long-flippered species suffered its greatest losses in the early 20th century, especially at the hands of Antarctic whaling fleets and shore stations in the Southern Hemisphere. About 1,000 humpbacks now range the northwest Atlantic, while probably fewer roam the European side. Some 3,000 survive in the southern oceans, fewer in the North Pacific.

RIGHT WHALE STUDY - In the early 1970s a research team, headed by Dr. Roger Payne and with support from the New York Zoological Society and the National Geographic Society, studied a rare band of southern right whales off the Patagonian coast in Argentina. From July to November each year, the whales gather in the shallow, sheltered waters to breed and raise their young.

RIGHT WHALE - Among the most endangered of the great whales, the right tody exists either singly or in small, isolated pids. Its slow speed and coastal habitat make it easy to catch. Though intensive hunting ceased in te 1920s, the species has been slow to show signs of recovery, Several hundred rights may ihabit the North Atlantic; a similar number live in the North Pacific. In the southern oceans a few thousand may still visit old whaling grounds. The map shading show only areas of reported sightings since the right's protection 1935.

INDIAN OCEAN - Modern whaling fleets have largely bypassed the northern Indian Ocean. As a result, only sparse information in available on its cetaceans. The Crozet and Kerguelen grounds in the south, once roamed by great numbers of right whales, have apparently never recovered from the convergence of American whalers in the 18th century.

TAGGING - Data on poulation and migration routes derive in past from tagging operations conducted by scientists in cooperation with the whaling industry. A coded ten-inch steel marker in fired into a whale's back, and a reward is offered for the return of the dart and any information about the tagged whale. In order to study live whales, scientists are introducing new, sophisticated methods such as radiotelemetry and satellite tracking.